Ready for Anything

Superior Pine Embraces a Growth, Diversification Strategy

By Les Shaver

Fall 2021

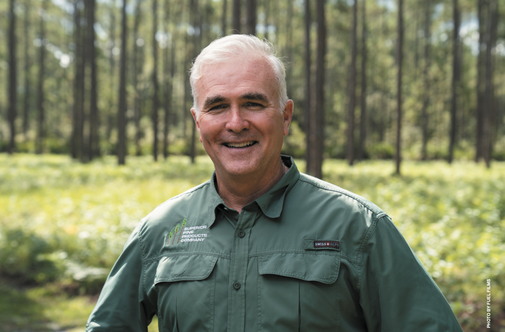

Scott Griffin, president and CEO of Superior Pine Products Company

Scott Griffin, president and CEO of Superior Pine Products Company

|

Georgia Forestry Magazine is published by HL Strategy, an integrated marketing and communications firm focused on our nation's biggest challenges and opportunities. Learn more at hlstrategy.com

|